After the disruption of the Civil War and the creation of the PRC, Chinese cinema continued under new management in the 1950s. It is estimated that up to 700 films were made in the period from October 1949 (when the PRC was established) to the onset of the Cultural Revolution in 1966 (which led to the effective closure of the film industry).

However, at an average of under 50 films per year this was no greater than the output at the end of the 1930s. The technical quality of films was much better (though you would hardly know it from the abysmal quality of the DVDs which were/are available) and many were now in colour rather than black and white.

But, in contrast to the vibrant industry of the 1930s and 40s (when censorship also existed), film making was now subject to strict censorship (and self-censorship). Unlike the Soviet Union and east European countries, where challenging films were still made despite the censor, Chinese censorship had (and still has) a deadening effect on the artistic quality of Chinese films.

For a very interesting (if arguably too positive) overview see the short videos for the festival A Revolution on Screen.

I have seen relatively few films from this period. Although, at least up to recently, films were widely available on DVD (many with English subtitles), the heavy emphasis on war films and/or cheerful workers was not attractive. (Many films are now available online but almost always without subtitles).

One of the more interesting genres was film adaptions of stories by May Fourth writers. I look here at four films by some of the most important writers, Lu Xun (1881-1936), Ba Jin (1904-2005), Mao Dun (1896-1981) and Ruo Shi (1902-1931). Although, all were prolific authors (and of course there were many more writers), very few of their works were made into films in this period.

The May Fourth Movement was an anti-imperialist, cultural, and political movement which grew out of student protests in Beijing on 4 May 1919. Although many of the authors associated with the movement were left-leaning, they were criticized by Mao Xedong and the CCP who felt that all literature had to be ‘in the service of the people’ (i.e. the CCP). Ba gave up writing fiction after the founding of the PRC but Mao Dun became Minister for Culture from 1949 to 1965. Both Ba and Mao were heavily criticized and persecuted during the Cultural Revolution.

Using the Douban database, it is interesting to note that of five leading authors (Lu Xun, Ba Jin, Lao She, Mao Dun and Shen Congwen), only 19 films based on their work were made during the seventeen years and, of these, 12 were in Hong Kong.

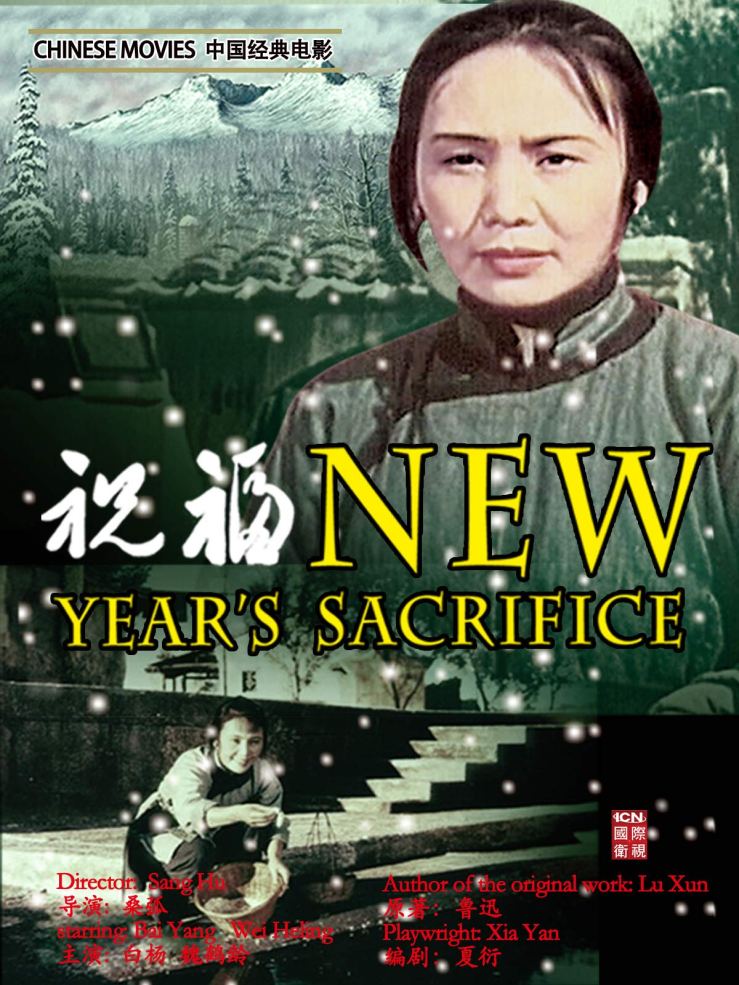

New Year’s Sacrifice [祝福] (1956)

Based on a Lu Xun short story (originally published in 1924), New Year’s Sacrifice [Director Sang Hu] is the tale of a poor woman in early twentieth century China.

Xanglin’s wife [Bai Yang] whose husband has recently died, runs away from home to prevent her mother-in-law selling her to a new husband. She takes up work as a servant with the wealthy Lu family in a nearby town. For a while all is well but then she is discovered and forced to return to her home. She is, as planned, sold against her will to a new husband in the mountains. But later the new husband dies and her son is eaten by wolves. She returns to the Lu family but is seen as an ill-omen and not allowed to participate in the important family rituals, In an attempt to atone for her sin (of losing two husbands) she donates a year’s salary to a local temple but this does not redeem her in the eyes of the Lu family and she is dismissed. Forced to become a beggar, she eventually dies.

The original story tells of how Xanglin’s wife is exploited and oppressed by all concerned in the old society: her family, the wealthy Lu family, religion and superstition. But the filmmakers clearly felt that Lu Xun was not precise enough in his story and altered several details to make the class aspect more apparent. In the story, Xanglin’s wife resists the forced marriage and is raped by her husband but in the film he is a kindly man who sleeps in another room on rushes on the wedding night. In the story he dies of typhoid but in the film he dies of overwork, oppressed by landowners and userers.

So what should be an vibrant story becomes a didactic tale. The filmmakers do justifiably change the perceptive from that of a young member of the Lu family in the story. In the film, the camera focuses on Xanglin’s wife. But, being a films from this period, there is little focus on her inner thoughts and feeling and Bai Yang is inexpressive in the lead role.

One might blame scriptwriter Xia Yan (himself a playwright and deputy Culture Minister at the time) for the changes to the story but he is also the writer on the much superior Lin Family Shop (below).

The film opens and closes with a reassuring voice-over telling us that this is the past and things like this could never happen in today’s China (shortly before the Great Famine).

The Family [家] (1956)

The Family is based on the Ba Jin novel (of the same name) published initially as a serial in 1931-2 and as a book in 1933. The story is about the four generation Gao family in the period 1916-20, set in a town on the upper Yangtze river (Chengdu in the book). The family is ruled over by the ageing grandfather, Old Master Gao [Wei Heling].

Directed by Chen Xihe and Ye Ming, the film focuses on the three brothers in the senior branch of the family (their father is already dead). The oldest Juexin [Sun Daolin] is the most complaint with the family rules and has married Ruiyu [Zhang Ruifang] although he was in love with his cousin Mei [the beautiful Hong Zongying in a rare post-1949 appearance].

The two younger brothers have more freedom to dissent. Juemin [Zhang Fei] is in love with his cousin Qin [Wang Yi] while the youngest Juehui [Zhang Hui] is the most rebellious and involved in student politics. He claims to be in love with the servant Mingfeng [Wang Dafeng] and tells her he wants to marry her (though he is careful not to let anybody else know).

The film focuses on the clash between the old Confucian society, exemplified by Old Master Gao, and the new freedoms sought by the younger generation who object to arranged marriages, narrow education for males only and Confucian principles.

The film follows the book in telling of the trials and tribulations of the younger generation with Juexin being faithful to his wife but realising that he still loves Mei who has returned to the town following the death of her own husband. When fighting breaks out between rival armies, she takes refuge in the Gao household. But her own health deteriorates and she dies.

Mingfeng is given as concubine to Old Gao’s aged friend, Mr. Feng (the head of the local Confucian Society). Mignfeng tries to get Juehui to help her but he is too occupied with his work. She throws herself in the family lake and drowns. Distraught, Juehui writes an article condemning the old ways!

Eventually, Old Master Gao dies but this leads to a further tragedy as the heavily pregnant Ruiyu is sent away to give birth as, in line with tradition, she cannot be in the house with the dead body. She dies in childbirth.

The film ends as Juehui leaves the family, sailing down the Yangtze to Shanghai.

The film works as melodrama and much of the acting is good. Some of the camerawork is excellent as the camera glides though the complex but confining Gao family compound. But the film is undermined by the acting of Zhang Hui in the key role of Juehui. He portrays Juehui as a sanctimonious cipher rather than a real person so that the character comes across as insufferable (all mouth and trousers).

The films avoids the social class didacticism of New Year’s Sacrifice but if one equates youth with the New China and old with the Old China, the message is clear: ‘new good, old bad’. And waverers like Juexin need to decide which side they are on. Ba Jin’s book was indeed intended as criticism of the old feudal society but he was too good a writer to descend to such a simplistic message.

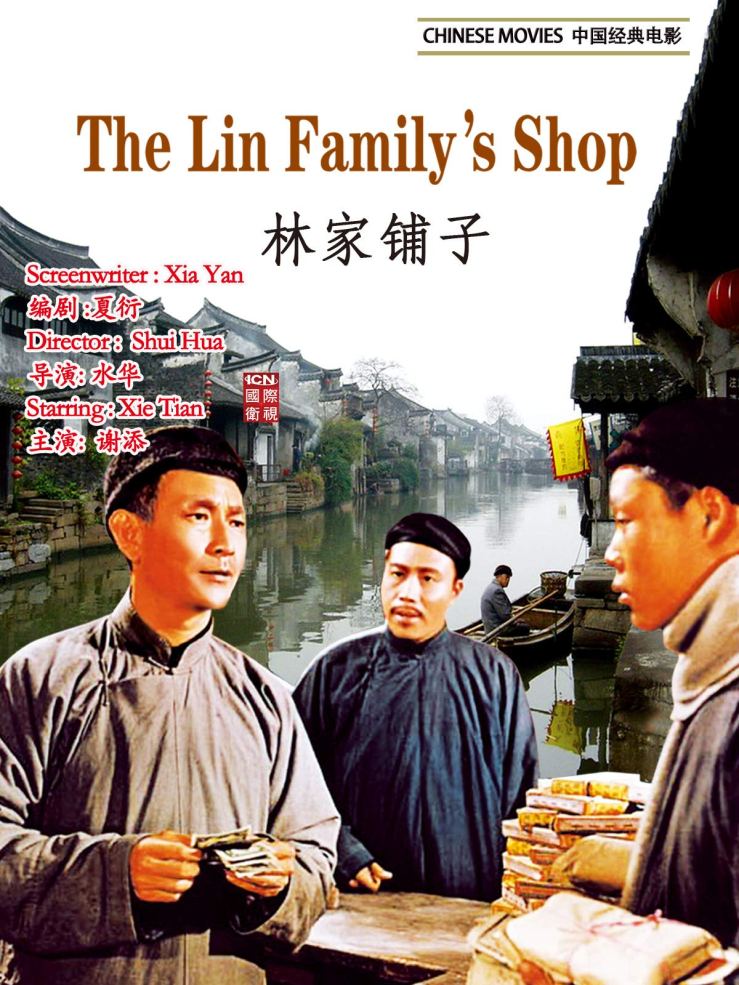

The Lin Family Shop [林家铺子] (1959)

This film (directed by Shui Hua) is based on a 1932 novella by Mao Dun. It tells the story of a small shop-owner in Zhejiang province struggling to make ends meet as the economy collapses and the Japanese increasingly encroach on China.

Mr. Lin [Xie Tian] owns a small general shop dealing in clothes and household goods. He is pressed for cash by his creditors while he has difficulty in making his debtors pay up. He bribes the local Guomindang officials to allow him to go on selling Japanese goods and cuts prices to increase sales which works for a while but, as he is selling below cost, the more he sells the more he loses.

He sells the last of his stock to refugees from Shanghai (under attack by the Japanese). (Typically, the well-dressed refugees from Shanghai are portrayed as having more money than sense.)

But with Shanghai under attack, his supplies and sources of credit are closed off. Worse, the local Guomindang Commissioner wants to take his 17-year old daughter Xiu [Ma Wei] as a concubine, as his two wives have failed to provide him with an heir. Lin decides to flee with any remaining cash and his daughter.

The film is a not unsympathetic account of this unlikely petty bourgeoisie protagonist. It does not explicitly condemn his actions even if it also shows the traumatic effect which it has on the small creditors who have invested money in his shop. Unsurprisingly, the film was severely criticized during the Cultural Revolution as being pro-capitalist and scriptwriter Xia Yan was sent to prison.

Xie Tian is excellent as Lin and the film, shot on location, provides a credible picture of a small bustling Chinese town of the period. The camera work is also much more fluid than normal. The only jarring note is twenty-four year old dancer Ma Wei as the daughter who looks more like a 50s film star than a seventeen year old shopkeeper’s daughter.

Unlike New Year’s Sacrifice, the film very closely follows both the story and the tone of the original. Mao Dun was Minister of Culture at the time and perhaps the filmmakers felt that they could not and/or did not need to rectify the story-line (scriptwriter Xia Yan was a deputy Minister of Culture).

Early Spring, February [早春二月] (1962)

‘Tyranny is worse than a tiger’

Early Spring (aka Threshold of Spring) directed by Xie Tieli is an adaption of a novel by Rou Shi who was executed by the Guomindang in Shanghai in 1931. It’s quite (pre-revolutionary) Russian in approach.

Early Spring (aka Threshold of Spring) directed by Xie Tieli is an adaption of a novel by Rou Shi who was executed by the Guomindang in Shanghai in 1931. It’s quite (pre-revolutionary) Russian in approach.

In the 1920s, Xiao Jianqiu [Sun Daolin] returns to the small Furong town (in Zhejiang province) to teach in the local school. He falls in love with the principal’s [Gao Bo] sister Tao Lan [Xie Fang] who reciprocates his feelings. He also supports the widow, Sister Wen [Shangguan Yunzhu], of a school colleague who had been killed in fighting in the nationalist Guangzhou uprising.

When Lan rejects a proposal from another teacher Qian [Wang Pei], son of a wealthy family, rumours start to spread about Xiao’s activities with the two women. Lan, who is also a teacher in the school, foils an attempt to boycott Xiao’s classes.

When Wen’s son dies, Jianqiu proposes, out of guilt, to marry her and support her, despite his love for Lan. But when Qian, trying to clear his path to Lan, suggest that Jiangqiu should do this, the fickle Jianqiu discloses his love for Lan. Wen solves his problems by killing herself (Shangguan Yunzhu was to do the same only a few years later during the Cultural Revolution).

Jianqiu goes off to throw himself into ‘the tide of the decade’ (possibly to join the Northern Expedition but given Jiangqiu’s lack of decisiveness I would not put money on it). Lan follows him.

The film is slow moving and uses small signs, such as Xiao and Lan walking in step or Lan playing basketball under the disapproving eye of other teachers, to make its points.

Jianqiu is the usual well-meaning but ineffectual male in these type of dramas. Lan and Wen at least know what they want but are unable to act as they wish in a male-dominated society.

Although the film is nuanced and rejects the usual good/bad dichotomy, it does labour its points. As had become common, and in contrast to the 1930s and 40s, many of the actors are much too old for their roles: both Sun and Shungguan are in their early 40s while even Xie (soon to appear as Chunhua in Stage Sisters) is in her late 20s.

The film is ostensibly quite apolitical (other than vague criticisms of the old society) and is really a May Fourth call for greater openness and acceptance. In the context of the time, this was presumably the political point of the film also. Taking an ostensibly apolitical story from a writer with an impeccable pedigree, the films also works as a call for greater openness in Chinese society after the disaster of the Great Leap Forward. But the film got caught up in ever-changing Maoist politics.

Zhuoyi Wang shows how the film-makers and Xia Yan tried to ‘improve’ the original story to make it more politically acceptable. But the lack of ostensible commitment to the CCP and class struggle led to it being labeled as a ‘poisonous weed’. Though Wang reports that Mao’s decision to allow it to be released for ‘mass criticism’ may have backfired as it was quite popular with audiences (if not critics).

The film, perhaps based on the novel which I have not read, is a combination of tradition and modernity. Jianqiu plays western music including Chopin (and the soundtrack is mainly western), and reads the New Youth magazine (linked to the New Culture movement). But he also quotes Confucius in his lessons. While at the start, Principal Tao extols the virtues of small towns versus the city, the rest of the film does not perhaps suggest that there is much to be said for small-town life.

For once a crisp print with vibrant colours (it’s from a CCTV broadcast which presumably indicates that clean prints of these films exist somewhere). The film shows a lot of location shots in a small town to add realism but otherwise remains quite stage-bound.

Overall, the four films, albeit all literary adaptations of works from the same time and context, adopt very different stylistic approaches. And politically, they are also very different. New Year’s Sacrifice distorts the original story for propagandist purposes; Family is more subtle but still simplifies the original message. Only Lin Family Shop avoids simple messages and is by far the best film as a result. Early Spring in contrast is a plea for greater openness which, of course, was only answered in the negative. But the films do show that censorship was not monolithic even in this period.

[…] as a book in 1933. It is the first mainland film version of the story with a second to follow in 1956. There is also a 1953 Hong Kong version which I have not […]

LikeLike