Chinese film in the 1930s and 40s was heavily affected by the context of war and revolution. The War of Resistance against Japanese Aggression lasted (albeit intermittently) from 1931 (when Japan occupied Manchuria) to 1945. After that came the civil war between the Nationalists and CCP.

In the mid 1930s about 50 films per year were being made in China. The Japanese partially occupied Shanghai (the centre of the Chinese film industry) in 1937. But filming continued partially as filmmakers moved from Shanghai (eventually to Chongqing, the eventual Nationalist capital) and partially within Shanghai (including the unoccupied foreign concessions). This phase ended in 1941 with the total occupation of the city.

After 1942, very few films were made in the territory occupied by the Republic of China, although filming continued in the Japanese-occupied areas including Shanghai and Manchuria. Pickowicz quotes a figure of 36 films made in Shanghai in 1943 but this likely dwindled to a low figure in 1944 and 45.

Film-making resumed slowly in 1946 but there came a flood of interesting and sometimes excellent films in 1947-49 despite the surrounding battle between Nationalists and Communists which led to the founding of the PRC in October 1949 (though the Communists entered Shanghai in May 1949 and took over the state studies in June). About 150 films were made in this period.

These included films which looked back over the war period including Spring River Runs East and Women Side by Side (though these were not ‘war films’ as such and as Pickowicz points out had relatively little footage of actual fighting). A second strand included films about the psychological and material difficulties of living in the difficult conditions of the time (though censorship generally meant that no explicit reference could be made to the civil war). These included Myriads of Lights and perhaps the best ever Chinese movie Spring in a Small Town. Then there were films which made no explicit reference to the political context such as Long Live the Missus.

This phase only lasted for just over than two years before it was smothered by the CCP take-over and a very different approach to film-making.

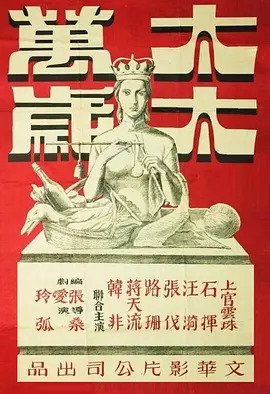

Long Live the Missus [太太万岁] (1947)

Long Live the Missus is a lively comedy of manners written by Zhang Ailing [Eileen Chang] and directed by Sang Hu.

Long Live the Missus is a lively comedy of manners written by Zhang Ailing [Eileen Chang] and directed by Sang Hu.

The film involves two families related by marriage, the Tang family, mother [Lu Shan], son Zhiyuan [Zhang Fa] and daughter Zhiqin [Wang Yi]; and the Chen family: eccentric father [Shi Hui playing well over his real age], mother [Lin Zhen], daughter Sizhen [Jiang Tianliu] (the central character) and son Sirui [Han Fei].

Sizhen is married to Zhiyuan and lives with his family. Her younger brother Sirui has just returned from Taiwan and falls for Zhiqin.

Initially the handsome but dull Zhiyuan is working in a boring bank job but, as a result of some creative storytelling by his wife, her father provides financial support and he sets up a successful business. But, encouraged by his friends, he is soon having an affair with Mimi [Shanguan Yunzhu] who is mainly interested in his money. Zhiyuan is not very good at secrecy and soon the entire family know what he is doing.

When Zhiyuan’s company becomes bankrupt, Sizhen has to decide on their future.

The script is sharp and the acting excellent. As might be expected with Eileen Chang as writer, Sizhen comes across as the commanding figure in the family negotiating her way though the Confucian family structure and ostensible male authority.

The film provides a strikingly different picture of marriage than that of 25 years earlier (for example in Jia). Women decide who to marry and whether (or not) to stay married.

While the film engages with gender politics, it avoids any obvious comment on the recent war or the surrounding struggle between the Nationalists and Communists; food including fresh fruit is readily available as are expensive clothes.

While the film engages with gender politics, it avoids any obvious comment on the recent war or the surrounding struggle between the Nationalists and Communists; food including fresh fruit is readily available as are expensive clothes.

Sizhen and Zhiqin appear in a series of gorgeous qipaos a la Maggie Cheung in In the Mood for Love, though the impact is less in black and white.

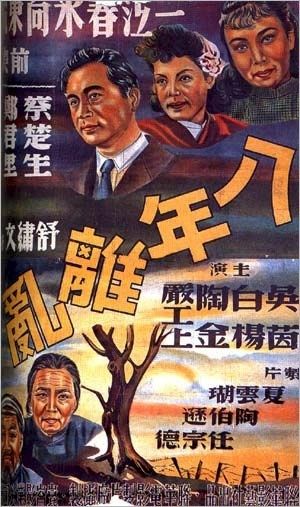

The Spring River Flows East [一江春水向东流] (1947)

‘How much sorrow can one person bear? As much as a spring river flowing east.’

The Spring River Flows East (aka Tears of the Yangtse) is a three hour epic in two parts which was released in October-November 1947 to enormous popular interest.

The story begins in about 1936 when Zhang Zhongliang (Tao Jin) is a patriotic factory official organising a concert to support resistance to the Japanese in the northeast of China. He is in love with and later marries Sufen [Bai Yang] and they have a child.

When war breaks out in 1937, he leaves to support the army in the medical corps and Sufen and his mother [Wu Jin] go to his home village which is later occupied by the Japanese.

The first hour of the film covers the war against the Japanese. Presumably for budgetary reasons there is little actual fighting but the directors [Cai Chusheng and Zheng Junli] use actual footage of death and destruction to good effect. Zhonglang’s father is hung by the Japanese and after the resistance (led by his brother) take revenge, Sufen, mother-in-law and child move back to Shanghai.

Meanwhile, Zhongliang (ironically his name includes the characters for loyal and good) has ended up in Chongqing (the wartime capital). Here he has landed on his feet. He meets his old friend Wang Lizhen [Shu Xiuwen] who has been ‘adopted’ by a rich businessman. She, in turn, adopts Zhongliang, gets him a job with her step-father and later marries him.

The film contrasts the luxury of a relaxed life in Chongqing with the hardships of Shanghai where Sufen is working in a refugee centre and the family struggle to survive.

When the war ends, Zhongliang returns to Shanghai but makes no effort to look for his family. He stays in Lizhen’s cousin’s (He Wenyan [Shangguan Yunzhu]) house and later her bed. Coincidentally Sufen takes a job as a maid with He and soon all is revealed.

Here one might expect Zhongliang to see the error of his ways and to return to his true wife and family. But he does not. Sufen throws herself into the Huangpu river in despair and his own mother disowns Zhongliang and pleads for a better future.

The film is an entertaining melodrama but with a much more challenging political message that one might expect. In particular the ending is very pessimistic (even though the second film is entitled ‘The Dawn’).

The film is an entertaining melodrama but with a much more challenging political message that one might expect. In particular the ending is very pessimistic (even though the second film is entitled ‘The Dawn’).

Given the film’s huge audience in late 1947 and 1948, one must assume that it reflects, and to some extent influenced, the audience’s own views. Presumably, the audience might have seen Zhongliang and his wealthy friends as representative of the ‘powers that be’ if not the Nationalist government itself; and Sufen, the mother and the rest of the family as the much put-upon ordinary people of China who had been betrayed.

Given the film’s huge audience in late 1947 and 1948, one must assume that it reflects, and to some extent influenced, the audience’s own views. Presumably, the audience might have seen Zhongliang and his wealthy friends as representative of the ‘powers that be’ if not the Nationalist government itself; and Sufen, the mother and the rest of the family as the much put-upon ordinary people of China who had been betrayed.

One disappointment is that the directors opt for such a stylised form of acting (or rather overacting). Tao looks and acts like a matinee star in a silent 1930s movie while Bai is all tears and long-suffering martyrdom. Wu hams it up in her regular role of the mother (in reality she was only six years older than her ‘son’ Tao).

Unlike say Women Side by Side or Myriads of Lights there are no ‘real’ characters but nor is there an idealised representative of the new China (other than Zhongliang ‘s brother and his wife who are minor charaters).

Myriads of Lights [万家灯火] (1948)

Myriads of Lights (aka Lights of Ten Thousand Homes) is set after the end of the war with Japan.

Myriads of Lights (aka Lights of Ten Thousand Homes) is set after the end of the war with Japan.

Hu Zhiqing [Lan Ma], an employee of a trading company, and his pregnant wife Lan Youlan [Shangguan Yunzhu] and daughter live in a a (smallish) apartment in Shanghai when his mother [Wu Yin] and extended family (5 in total) come to stay, fleeing poor conditions in the country.

This is a family drama set in the post-war period with high inflation and job insecurity (implicitly during the civil war). Initially much of the focus is on the clash between urban and rural values (the visitors bring lice!). The shortage of space and lack of money also create tensions. The kind but spineless Hu and his wife Youlan pawn their goods to make ends meet.

Business is portrayed as corrupt: Hu’s boss Qian [Qi Heng] (who comes from the same town) plans to put the company into liquidation and start again under a new name. He refuses Hu a loan while hiring young women to accompany him on nights out.

The tension between national and foreign business are also highlighted. The family have to leave temporary accommodation as it is rented for the storage of imported American goods while another character’s job is threatened by imported pharmaceuticals.

As winter approaches things get even tighter and food gets scarce. Hu loses his job. Youlan has an argument with the stubborn mother who threatens to move out. In the end Youlan leaves to say with friends and Granny and the family move in with a more distant relative. But then Youlan has a miscarriage.

The increasingly desperate Hu tries to take a wallet on a bus but is beaten by his fellow passengers. Attempting to escape, he is, symbolically, run down by Qian’s car.

For most of its duration, the film is a very downbeat example of ‘melodramatic realism’ reminiscent of some US movies of the 1930s. But we get a final, not-very credible Hollywood-style reconciliation between Youlan and the mother. The sick Hu turns up to overhear his ungrateful mother criticising him for his indecision and saying he should be more like other relatives who are willing to help everybody! But he is reassured that it is all somebody else’s fault and that things may get better!

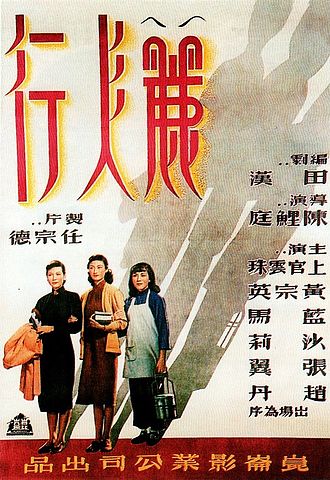

Women Side by Side [丽人行] (1949)

While Spring River Flows East is (relatively) well-known as the classic exposition of experience during the War of Resistance against Japanese Aggression, Women Side by Side is a nuanced and fascinating account of life in occupied Shanghai in 1944, shot largely on location. It was released in January 1949.

While Spring River Flows East is (relatively) well-known as the classic exposition of experience during the War of Resistance against Japanese Aggression, Women Side by Side is a nuanced and fascinating account of life in occupied Shanghai in 1944, shot largely on location. It was released in January 1949.

The film, based on a play by Tian Han and directed by Chen Liting for the Kunlun Film Company, tells the story of three women: middle-class Ruoying (Sha Li], resistance worker Xinqun [Huang Zongying], and working class Jinmei [Shangguan Yunzhu] (left to right in the poster and below).

Jinmei is raped by Japanese soldiers and is assisted by Xinqun who bring her to the home of her former classmate Ruoying. Jinmei loses her job because of the rape and her husband is later blinded in a fight. She become s sex worker to support her husband and his mother.

Ruoying’s husband Yuliang [Zhao Dan, in real life the husband of Huang Zongying] left Shanghai in 1937 to move to the Nationalist area leaving behind his young daughter Beibei. Ruoying eventually moved in with banker Wang Zhongyuan [Lan Ma] who considers himself neutral, i.e. he will do business with the Japanese but does not support them politically.

Ruoying learns that Yuliang is returning to Shanghai after seven years to see his daughter and they arrange to meet in Xinqun’s apartment. But when the Japanese arrive, searching for resistance fighters, they arrest Ruoying and Yliang by mistake. Taken to prison, Yuliang is tortured.

Xinqun asks Zhongyuan to use his contacts to get them out which he does agreeing, in return, to help the Japanese establish a publishing house. Typically, being Shanghai people, Ruying, Yuling and Bebei go immediately to Little Paris cafe for breakfast.

Jinmei’s husband discovers the source of her earnings and throws her out while Ruoying finds out that Wang has been sleeping with a woman also sexually involved with a Japanese official. Both consider suicide but are convinced by Xinqun of the need to fight to become modern women.

The film is too melodramatic to be an entirely realistic portrait of life in occupied Shanghai. But it is amazingly balanced for the time.

There are no ‘good’ characters (except the idealised Xinqun) and (with the exception of the Japanese) no bad characters (there is even a kindly old Japanese man).

Wang is portrayed in nuanced terms and Ruying and Yuliang are remarkably understanding given that she clearly feels she was abandoned by him while he feels she has been living it up in Shanghai while he has been struggling ‘on the front line’. Only Xinyun and her husband Meng Nan [Zhou Feng] are idealised characters but they are intended to represent what the new China should strive for (Xinqun literally meaning something like ‘new masses’).

Presumably it was the nuance and the refusal to adopt pre-ordained class positions that contributed to the film being denounced as a ‘poisonous weed’ during the Cultural Revolution. This might seem almost funny now but not so much for director Chen and scriptwriter Tian who both went to prison in the period (as did Zhao Dan). Tian died there. Shangguan Yunzhu committed suicide in 1968.

There is a restored version by the Chinese Film Archive which would be nice if one could see it. The version I saw was of very poor quality with sometimes incomprehensible subtitles.

While many Chinese films have more than one English title (often unrelated to the Chinese title), this movie is endowed with numerous names. It has been referred to as Three Girls/Beauties/Women; Female Fighters and Women Walk Together.

Crows and Sparrows [乌鸦与麻雀] (1949)

Crows and Sparrows tells the story of a group of people living in a Shanghai house in late 1948-early 1949 as the civil war between the Nationalists and Communists drew to an end (Shanghai was occupied by the Communists in May 1949).

Crows and Sparrows tells the story of a group of people living in a Shanghai house in late 1948-early 1949 as the civil war between the Nationalists and Communists drew to an end (Shanghai was occupied by the Communists in May 1949).

Filmed during 1949 and released in November 1949 (just after the establishment of the PRC) the film adopts a strongly anti-Nationalist tone.

The occupants of the house include the villainous landlord (the crow) Mr. Hou [Li Tainji] (formerly a collaborator and now senior Nationalist official) and his wife [Huang Zongying]; and the tenants (sparrows) including the intellectual teacher Mr. Hau [Sun Daolin] and his wife [Shangguan Yunzhu]; the former owner of the house Mr. Kong [Wei Heling]; and the Xiao family who run a small shop [Zhao Dan and Wu Yin again].

It soon becomes apparent that Mr. Hou will be selling the house as the Nationalist government collapses and the tenants scramble to retain their lodgings and/or find new ones.

The film was positively received at the time, and since, including by official Chinese critics.

However, there is a lack of drama (not melodrama) and characterization in the film. Mr. Hou is a stereotypical evil landlord of the type we were to see much more of in the future (Huang Zongying is largely wasted in the tole of his wife). The tenants are more credible with Mr. Hau vacillating between the different sides unable to decide who he can afford to offend. His wife is more focused on maintaining a home and fending off the advances of Mr. Hou. The Xiao family attempt to buy out the house but are more for comedy purposes while the kind but ineffectual Mr. Kong makes the right noises without doing very much.

Eventually, Hou is forced to flee and the tenants gather together to celebrate the Chinese New Year and to welcome the new society.

There is no real dramatic conflict between the crow and sparrows because the latter are portrayed as powerless and the issues are resolved by the victory of the off-screen Red Army rather than by any real character developments on screen.

The film is interesting for the circumstances in which it was shot and it perhaps gives some impression of the challenges of living in Shanghai in 1948-49 (with rapid inflation and total political uncertainty). In successive scenes the film contrasts food riots with Mr. Hou’s plush cafe. However, it is ultimately not totally successful as cinema.

Despite his attempts to reconcile with the new regime, director Zheng Junli died in prison in 1969.